"To Be" or Not "To Be" – How and When Should You Be Incorporating Writing Advice into Your Style

Written by Zoë Rose Wright

Updated: May 23, 2023

First published: May 22, 2023

Good writing advice is highly valuable to writers at any level. But what do you do with the advice that challenges your writing style?

Writing advice is the most valuable component of all creative writing courses and workshops. Our peers and mentors all contribute to these environments through a blend of spontaneous and informed advice. However, every creative writing mentor has that one hill that they are willing to die on. For some it’s adverbs. For some it’s dialogue tags. For others, it might be passive tense or “show don’t tell.” Regardless of what it is or why they want you to adopt it, every writing instructor has at least one crusade they want to introduce to their students. Although these lessons can help students recognize the hidden clichés and weaknesses in their writing, these undiluted approaches to writing can severely limit a writer’s ability when they aren’t taught how to reincorporate these structures into their writing. After all, if every professor or writing coach has at least one quirk, and the writer comes into contact with at least five of these mentors during their journey, that removes five “weak” structures from their writing for no reason other than “it looks unprofessional.”

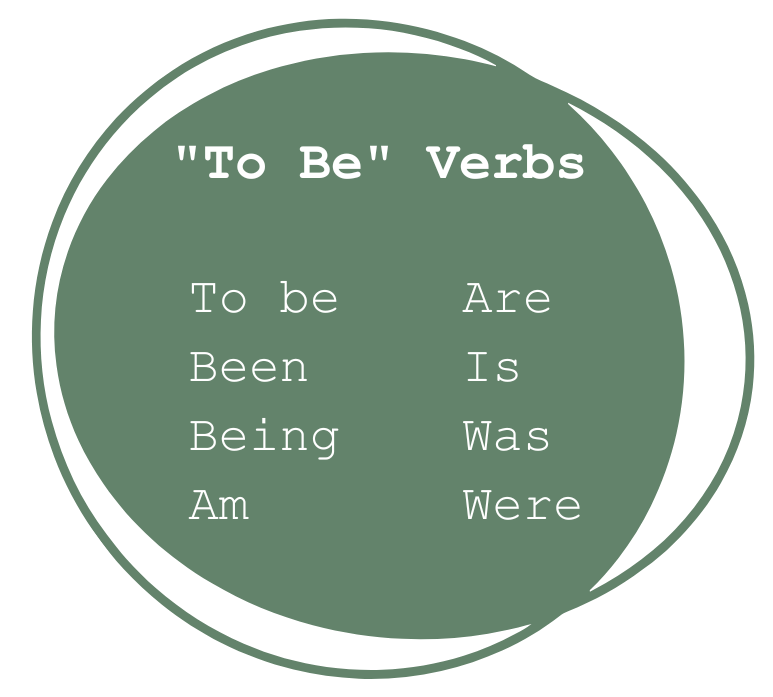

At one point, I had a mentor whose quirk was “to be” verbs. Once they spotted the first usage, they would flag every one thereafter, regardless of its context within the passage. For those in need of a refresher, these are the “to be” verbs:

Now, perhaps I’m just that poor of a writer, but I was hard pressed not to use these fundamental verbs and contractions at least once every five pages or so. I did notice some an uptick in creativity in response to this challenge, but to use none of these words at all? I am a firm believer that every opportunity—positive, negative, or just plain underwhelming—can become a learning opportunity if you approach it as one. So, I chose to reflect on what I was doing to meet this standard while also considering what this course was doing for me.

Writing to Learn

This experience happened during a genre writing course I took roughly three years into my academic journey. It was a wonderful course. I actually took this exact course two more times to generate additional portfolio material. For the final assignment, I had submitted a 23-page draft. Written in a blind passion and edited like my life depended on it. It certainly felt like it did. This was my first year as the Editor-in-Chief of a local literary journal, and I had everything to prove. I can’t even remember the plot without digging up my old thumb drive, but I remember the confidence that my mechanics were pristine.

Now, I had workshopped with this professor for several years at this point, and I knew their peeves and what they looked for in a draft. With this in mind, I selected every single word and punctuation with a purpose. I sent this short story to friends and colleagues. I read through it backwards, paragraph by paragraph with pages shuffled. By the time I had submitted it, I had stared at this document for so long that simple scenes were starting to feel like formulas and equations. I couldn't imagine the draft looking any other way. To change so much as one adjective would change the context of an entire passage. Once I got my feedback, I’ll gladly admit that it was remarkably clean… except for the "to be" notes. There were seven of them. In 23 pages (22.5, for total transparency) I had seven instances of "to be" verbs. But I had written myself into a corner, I had tightened my draft so thoroughly, that to remove them and still be grammatically correct, I would have to revise the surrounding passage of each usage.

It was disheartening to receive this. As gratifying as it was to see the clean document, these few comments, robotic and without any additional feedback, left me feeling that my writing had been reduced to these seven moments of weakness. I was so proud of this story and my ability to meet the professor’s standards, and all they had to say was “strike ‘to be.’”

In these scenarios, these rules are often enforced without discretion to help students break weak writing habits within the brief time the mentor has with them. I didn’t expect any of these people to go on without using a “to be” verb ever again. Rather, they would go forward using these typically “invisible” verbs consciously and with intent. That said, at no point in any of my courses did my professors ever reinstate permission to revisit these words or mechanics. Without this permission, my peers and I would often leave with one of two takeaways:

- Disregard entirely. This was bad advice. They don’t know what they’re talking about.

- Join the crusade. I respect this mentor. They have never steered me wrong.

These are extremes. An “all or nothing” commitment, like my mentor, disregards context for the sake of making a point. This can lead to decisions in your writing that you can only support through principle. In other classes, I could see the product of these experiences in writers whose style had become disjointed. They took fantastic risks in their works, but avoided convention and practicality at all costs. There was no balance. Without “weak” writing to help readers orient themselves, these writers had set unintentionally high requirements for entry and enjoyment of their work.

Learning to Write

In a classroom environment, you are taught to recognize these quirks of “weak” writing and purposely remove them from your drafts until it becomes intuitive. This is similar to the process of identifying a complex food allergy and removing it from your diet. However, we aren’t all allergic to the same thing, so it doesn’t make sense to remove these quirks on the off chance that we or our audience are. Every so often in your journey, you should take time to reflect on all the things you have removed from your writing “diet” and add them back in, one at a time, until you are only excluding what truly isn’t a good fit for you. Emphasis on “you.”

First, don’t write yourself into a corner. These writing exercises are lessons in the extreme, and you need to make sure your writing is flexible enough to experience the lesson at hand. Like in physical exercise, if you remain completely tense during this process, you will get hurt. I pride myself on being emotionally open to edits, but I was so fixated on that draft that it felt like the slightest revision would change the rhythm of the piece. Plenty of writing gurus tell you to put your draft in a drawer in order to gain distance, but that doesn’t help if you can’t see the draft any other way than it is. Walking away from a draft isn’t enough to achieve distance. You have to walk away before revising at all.

Second, if you have any tenets of “great writing” that you’ve been holding onto, take a moment to identify them. Did your high school teacher hate the Oxford comma? Did that one person from that one writing group tell you that any sentence over 3 lines long is a run-on? Did a beta reader tell you that your dialogue tags weren’t varied enough? Take stock and consider how these comments have impacted your writing. Do you follow any of these tips? Do you discard them? Do you feel guilty about your decision?

During coaching sessions, I like to approach these baked-in writing habits through reflection first, action second. Rather than simply identifying the quirk and doing whatever you think the opposite is, think first about where and why this entered your writing style.

- Make a list of any writing advice you think of often (positive or negative).

- Identify what this advice is supposed to accomplish and why it would be beneficial to your writing.

- Now look at this advice and consider the opposite, the antithesis. What would it look like to ignore that tip or break that rule?

- Take moments to actively challenge these rules in your writing. Start with something low stakes, whether it’s during a warm-up exercise or a short story or something else, working your way up to doing this during larger, more visible projects.

It will probably take a while before you become more comfortable with writing “against the grain.” We learned these quirks from mentors and whether that relationship ended positively or negatively, these are people that have held our respect.

This is an act in recognizing that there is no such thing as definitively bad writing. Craft and skill are contextual. Writing that fails with one audience will succeed with another. These structures are “weak” because they are used so much in regular communication and become effectively invisible in certain settings. Know your context. Let go of the writing advice that is challenging it.

Have any questions or topics you would like me to discuss? Let me know at asktheeditor@rosewrite.com